The look that hides an old attribution to Goya

Dark eyes full of strength stare at the viewer. They look almost like a beacon within the canvas, totally enveloped in shadows where the brush strokes of the wig and dress intertwine with the background itself. The enigmatic look that the lady possesses is perhaps the main reason why academics a century ago chose her as part of the Goya 1900 exhibition, already as referenced in the supplement to the exhibition catalogue.

Today we cannot say that it is an autograph work by the Aragonese master, but it is at least an interesting question that for almost fifty years it was considered as such by the academics of the time. Among these scholars it is worth mentioning Aureliano de Beruete y Molet, director of the Prado Museum from 1918 to 1922, who included him in publications such as “Goya painter of portraits” 1919.

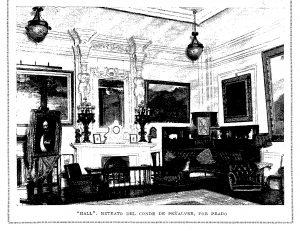

As they appear in all the publications from 1900 to the 1950s, the painting is titled “unknown lady” belonging to the collection of the counts of Peñalver. It is worth noting its origin since at that time the then count was Don Nicolás de Peñalver y Zamora. Born into a rich and old family from Havana. Installed in Spain, he would hold the mayor’s office of the city of Madrid up to three times around 1900. Known, among other things, for being the instigator of the famous Gran Vía, which in fact bore his name for a while. It is worth mentioning that in a newspaper article in the magazine Blanco y Negro on June 7, 1925, the then widowed countess opened the doors of her Madrid palace. In the report you could see part of the interior of the mansion with luxurious rooms and mentions of the works of art in the collection, among which “Goya’s head” is cited. Currently the palace remains standing on Calle Rey Francisco, being one of the oldest buildings in the Arguelles neighborhood.

Of all the publications where the work is mentioned, none of them delves into its dating or its context within Goya’s production. Beyond treating its authorship and the name of the portrayed, we can locate it around 1790, thanks to the features of its hairstyle and its clothes. We could compare it with two female portraits from 1793, Ceán Bermudez’s wife and the Marquise de la Solana. Both present a headdress with their own dark hair raised and crowned by a small flower decoration that in our case is barely sketched, almost intuiting the petals and shapes. The pigment analysis carried out has also confirmed that it was executed in the last years of the 18th century.