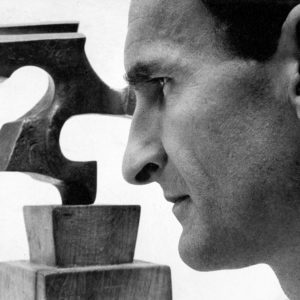

Chillida: a creative force arising from nature.

Among the rocks and the waves of Ondarreta beach in San Sebastian emerges the famous “Peine del viento”, one of the monumental public sculptures with which the artistic voice of Eduardo Chillida made itself felt throughout a continent European, in full transformation. The premises on which the Basque sculptor built his creation seem determined by the landscape and the relationship with the natural environment where he spent his childhood. Next to the sea, the reflections around the concepts of space and time crystallized under which he founded a work forged in the brotherhood of the eternal rhythms that he found observing the tides of the bay of San Sebastian. However, it would be unfair to limit only to sculpture the international prestige and recognition that the San Sebastian artist achieved, whose work is also celebrated for the use of multiple artistic practices that, like collage, he developed throughout his vast career. Through works such as the one that concerns us here, we construct a deeper and more complex story that sheds light on the true magnitude of the creative universe of which it has been, one of the key figures in the radical transformation that Spanish art experienced during the twentieth century.

Under this premise, the collage made in 1967 is a magnificent example of Chillida’s undying fascination for the concepts of space and form, whose reflections and approaches in this regard are materialized in his sculptural work and which, in an equally masterful way, he manages to convey to the world of the paper. In this regard, his academic training in the field of architecture played a determining role from which a deep interest in making space visible through the consideration of its surrounding forms would take root. His research in this regard is linked to the postulates by Martin Heidegger, whose philosophical reflections on the shape of the void have been recognized as the theoretical basis of the so-called Basque School in which Chillida’s work is inscribed.

Under this premise, the collage made in 1967 is a magnificent example of Chillida’s undying fascination for the concepts of space and form, whose reflections and approaches in this regard are materialized in his sculptural work and which, in an equally masterful way, he manages to convey to the world of the paper. In this regard, his academic training in the field of architecture played a determining role from which a deep interest in making space visible through the consideration of its surrounding forms would take root. His research in this regard is linked to the postulates by Martin Heidegger, whose philosophical reflections on the shape of the void have been recognized as the theoretical basis of the so-called Basque School in which Chillida’s work is inscribed.

In the two-dimensionality of these works on paper, underlies the essence of the inseparable sculptural substrate, endowed, however, with its own entity that is not subordinated to any other purpose. His collages, masterfully constructed from the superposition of pieces of paper interconnected with each other almost organically, give life to rhythmic compositions in which he constructs a space for dialogue, where antagonistic concepts such as materiality and weightlessness converge or the solid and the ethereal. While the specific qualities of the paper and its texture underline the material and corporeal aspect of nature, the interactions between the burnt irregular edges suggest its metamorphic and ephemeral character. Underneath this intrinsic duality to the natural world, there is also the dichotomy that Chillida faces us in a debate between the knowledge of the laws imposed by nature and the human aspiration to transcend them. In short, “we are nature, but we want to get rid of its obstacles.” His is, therefore, an ethereal materiality, the result of a deep and complex relationship with nature that, understood as a source of primal creation, also encourages us to experiment with its own limits. Heidegger precisely said that the border is not what something ends at, but rather that from where something begins to be what it is. It is in this space that transcends the limits, where Chillida builds a work worked from the nakedness of form and matter that, folded back to its original essence, is freed from its own borders to head towards the conquest of a total space.

Eduardo Chillida was the best apprentice the sea could have. In front of him, he internalized the effect of erosion that shapes the edges of the rocks, that flow of water that penetrates between its hidden fissures, that calm sea that churns between the blowing of the wind. His works emerged under the indomitable cadence of the Cantabrian rhythms to capture in them, the space where everything is born and everything is broken. The same where, as he described “in a line the world is united, and with a line the world is divided.